WPA Collection

The Oklahoma Art Center, a predecessor of the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, was incorporated on May 18, 1945, but its story begins with the opening of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Experimental Gallery in downtown Oklahoma City in 1936. The WPA was created in 1935 to curb the mass unemployment of the Great Depression, and while it mostly focused on improving the nation’s infrastructure, its Federal Art Project (FAP) provided substantial resources for artists and established over one hundred art centers around the United States. Included among these was the WPA Experimental Gallery, which would later become the WPA Oklahoma Art Center when the government funded a new, larger space in the Civic Center’s Municipal Auditorium under Nan Sheets, a well-known artist and this Museum’s first director.

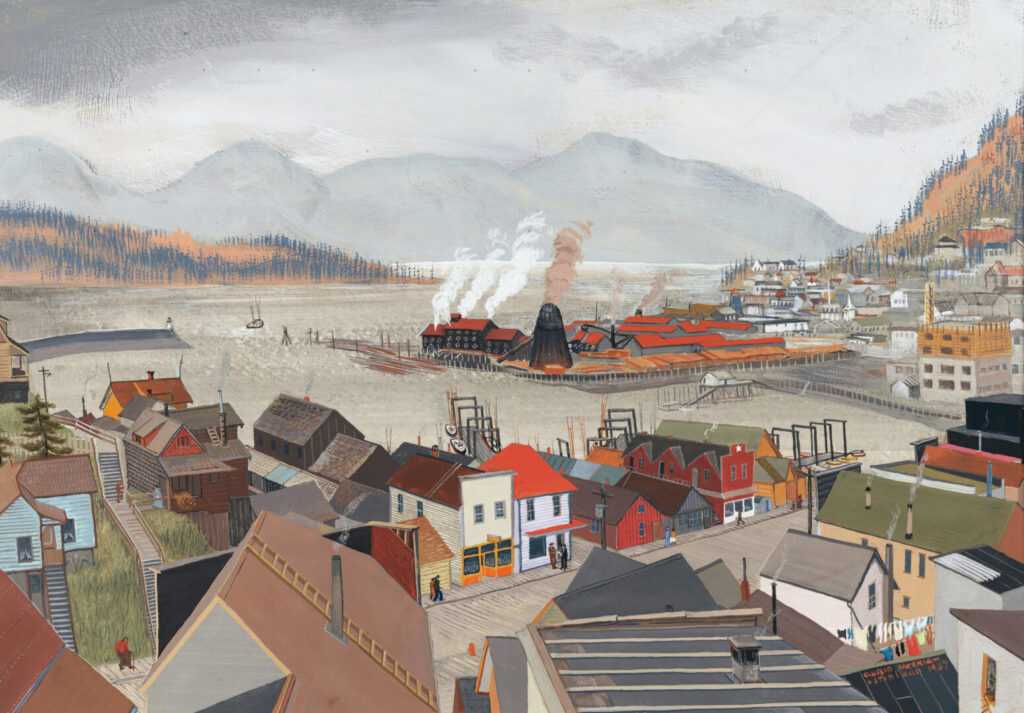

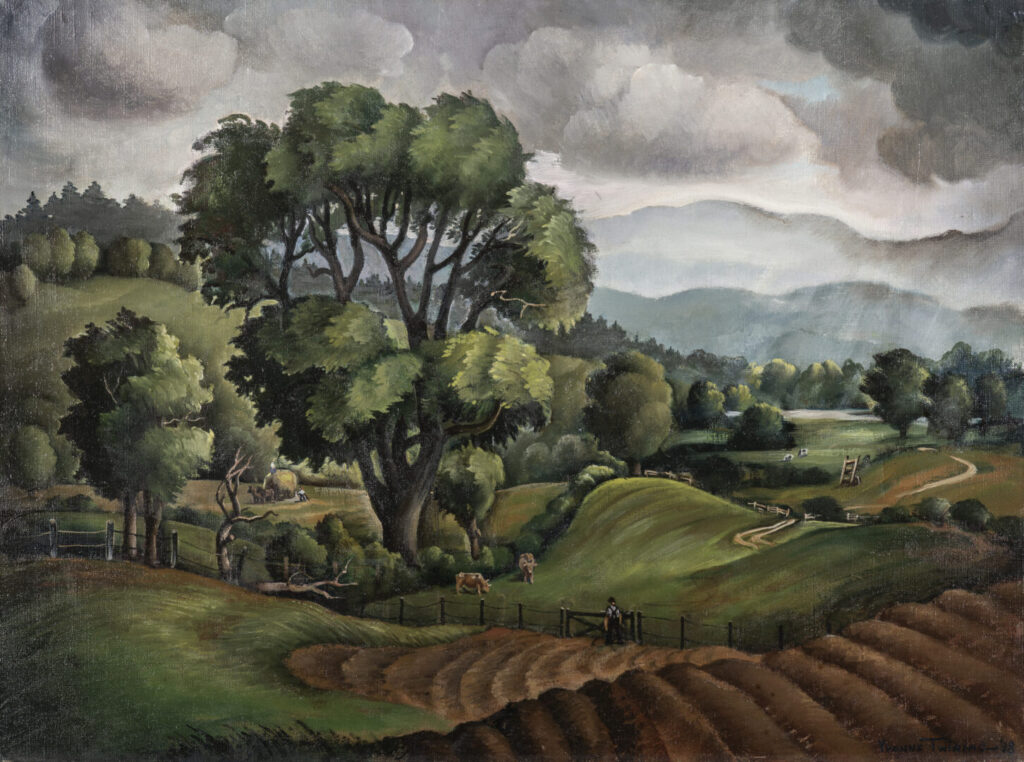

In the 1940s, the Oklahoma Art Center began acquiring art and displayed exhibitions at the Municipal Auditorium. When the WPA began to dissolve in 1942, the Oklahoma Art Center became an independent entity and the FAP’s Central Allocation Unit gave twenty-eight works by twenty-six artists to the city of Oklahoma City, providing the basis for the Museum’s new permanent collection. As seen in examples in this section, OKCMOA’s WPA Collection features many rural American landscapes and depictions of labor, infrastructure, and industrial development. All are figurative, as was favored by the WPA, and there are significant numbers of women and foreign-born artists in the Museum’s founding collection, as well as artists with local ties, such as Muscogee (Creek)/Pawnee painter Acee Blue Eagle.

Several of these works can be found in the Museum’s second-floor galleries.

About the artsits

In 1937, American magazine declared Acee Blue Eagle the nation’s “foremost living Indian artist.” Blue Eagle was born thirty years earlier on the Wichita Reservation near Anadarko, Oklahoma. After graduating from the University of Oklahoma, he was employed by the Federal Art Project to paint murals throughout Oklahoma. He later served in the US Army Air Corps.

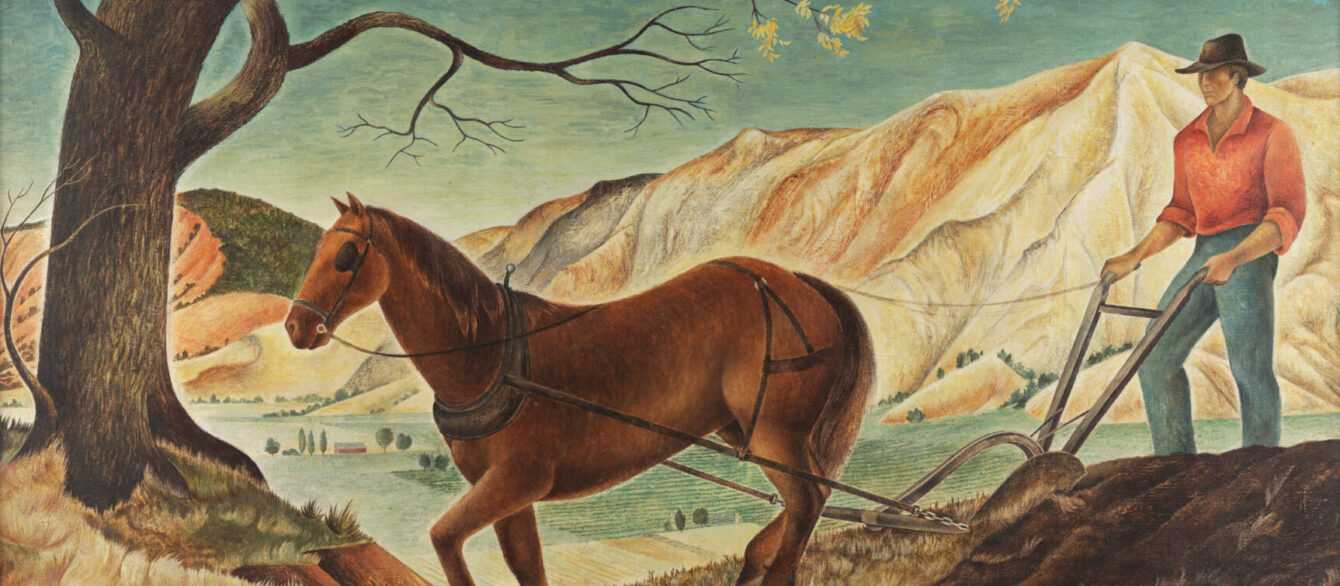

Cameron Booth studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and later in Munich, Germany with the influential Abstract Expressionist Hans Hofmann. During the 1930s, the WPA employed thousands of people on public works efforts. These projects, which provided the core of the WPA’s relief effort, inspired Booth‘s subject matter.

Artist Raymond Breinin was hired by the WPA to paint murals in schools, hospitals, and hotels. He often worked in a Surrealist style, creating dream-like scenes.

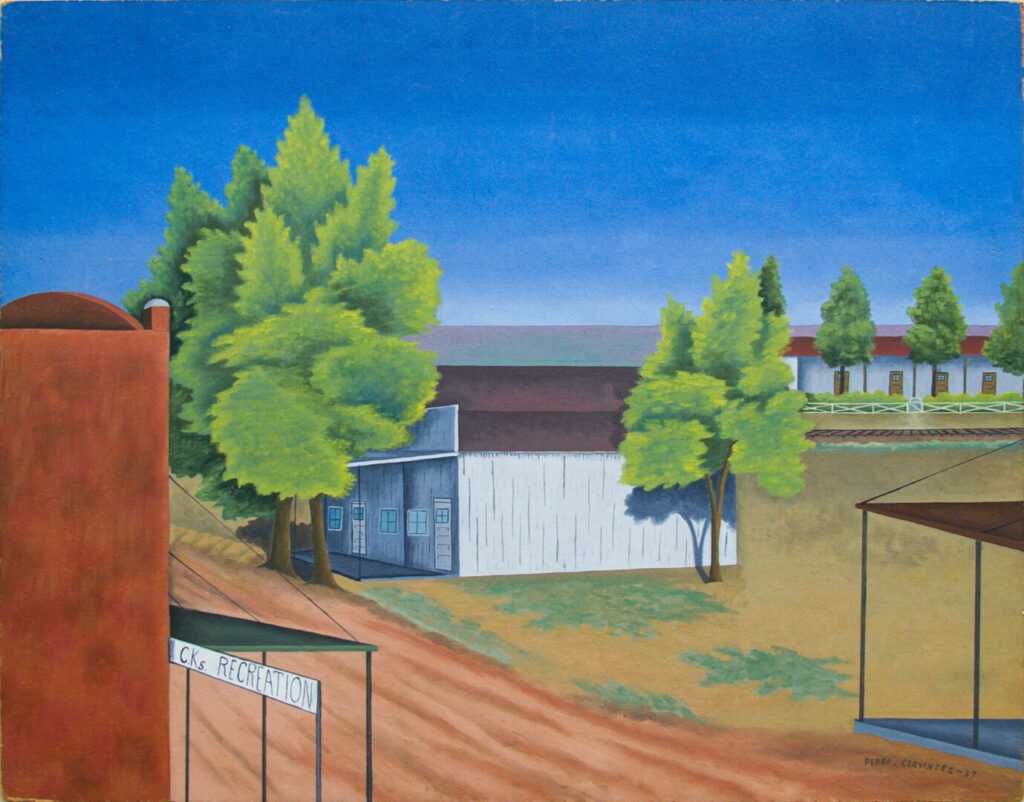

Pedro Cervántez was among the first Hispanic artists in the United States to receive national recognition. After assisting with WPA murals, he was hired as a painter with the Federal Art Project.

Leon Garland immigrated to the United States from Russia at age seventeen. He settled in Chicago, studied at the Art Institute, and later found employment with the WPA.

Gottlieb was actively involved with the WPA and was the president of the Artists’ Union, an organization that lobbied for federal support for artists. A Social Realist painter and printmaker, Gottlieb depicted the working conditions of laborers.

Originally a student of American realist Robert Henri, among others, Kantor worked in an abstract Cubist style in the 1920s, before turning to more romantic, representational depictions of American life during the Great Depression.

Born in Oakland, California, in 1911, Dong Kingman returned with his parents to their native China when he was five. At age ten, Dong began attending painting classes in Hong Kong under the direction of Sze-to Wai, a well-known painter who had studied in Paris. The

Chinese-American artist returned to California at age eighteen, working a number of odd jobs before winning acclaim as a watercolorist with his first solo exhibition in 1935.

Jenne Magafan was a WPA Federal Art Project painter and muralist. Among her awarded mural commissions were post offices in Nebraska, Kansas, and Texas.

Twining was one of many women who had the opportunity to thrive under the Federal Art Project, thanks in part to WPA Director Holger Cahill’s egalitarian stance towards hiring. The New York City-born artist worked at least eight hours a day, completing nearly seventy paintings and drawings between 1935 and 1942. Accordion Content

As the Great Depression advanced in the early 1930s, Dorothy Varian, like so many artists of her generation, was able to continue working from the subsidy provided by the Federal Art Project. Unfortunately, most of her work from that time has been lost.

Image Credit: Jenne Magafan, “Ploughing (detail),” 1937, oil on canvas, 19 x 30 in., Oklahoma City Museum of Art, WPA Collection, 1942.022, Image by Google